There has long been the somewhat naive belief that hard times create good music. Awaiting the influx of aural gold has been a silver lining many have clung to since the pandemic. But with the economic collapse threatening to close music venues and recording studios, pricing many punters out of gigs, and generally reducing consumer confidence, it is becoming increasingly more evident that in its current commodified state counterculture only thrives in stable financial times.

Realising that counterculture relies on the whims of a late-stage capitalist government is a pretty bitter pill to swallow; it is better to choke it down at this stage of the game before our respective culture bubbles burst completely. Scenes around the UK are already starting to feel increasingly fractured, with many artists only going to local gigs if their names appear on the bill – something that I haven’t been able to ignore since the return of live music in July 2021.

Creativity is infinite, but as we start to move away from community and collectivism toward individualism, it is painful to see acts of creativity existing as random, isolated feats of ingenuity as opposed to the lifeblood of anti-establishment movements. And I am not alone in being aware of the fragmented state of the music industry and its respective scenes.

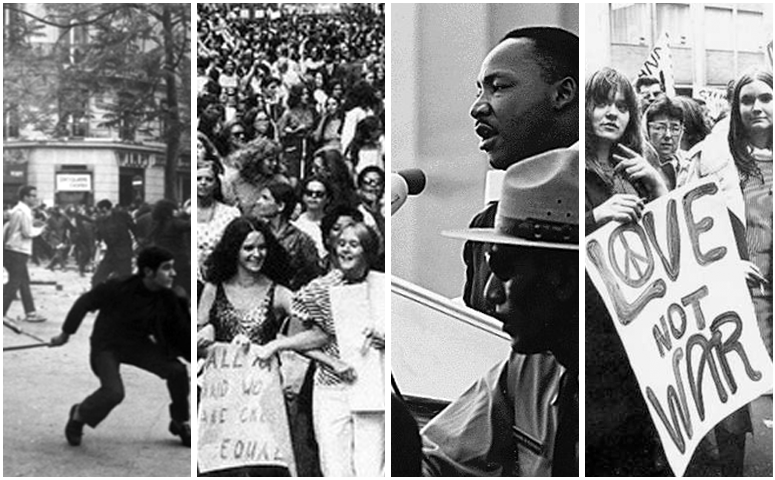

The author, academic and musician Alex Niven pointed out that even if we look to the 70s, a reportedly bleak chapter in UK history which saw the rise of the UK punk movement, we still had a well-funded public sector and it was the height of equality in Britain. The same can not be said for 2022, following the last mini-budget that has desecrated the pound, widened the rich-poor divide, and instilled even more fear into minds already frantic with anxiety.

While some artists are still able to amass staunch followings, sell-out tours and their physical music releases, the music industry as a whole is suffering under the weight of the crumbling infrastructure. The void of anti-establishment counterculture is also painstakingly evident when we look at the lack of protests in the UK. Our protestive apathy puts plenty of weight behind Simon Reynolds’ 2009 statement, “The next big thing could be that there is no next big thing… just further entropy”.

I have previously written on how to recession-proof your music career, but it is becoming increasingly more evident that the community side of music is disintegrating around the pervasive self-interest of many independent artists. Music has been bringing communities together for far longer than it has been a commodity for artists to make money and grab glory off the back of. Music and society have always been interlinked; music has helped to promote and protect human rights, drive social change, document history, and facilitate communication. Given our precarious current times, we need more of that than ever.

In commercial terms, it is clear that things are going to get worse before they get better, especially if we heed the warning of the CEO of UK Music, Jamie Njoku-Goodwin, who is already anticipating 2023 to be worse than 2022 for the music industry. What better time for artists to reevaluate their positions in their scenes and start to find ways of bolstering communities? In this era, it will be the artists able to bring meaning to their fans’ intrepidly anxious existence who get to thrive.

Article by Amelia Vandergast

No Comments