Marilyn Manson is back on the scene after getting sober, but even if he never touches another drop, there’s no way of his reputation coming clean after the spate of emotional, physical and sexual abuse allegations brought against him.

The most notable allegations came to light in February 2021 when actress Evan Rachel Wood publicly named Manson as her abuser on social media. Wood had previously spoken about being a survivor of domestic violence in her testimony before a House Judiciary Subcommittee in 2018, aiming to get the Sexual Assault Survivors’ Bill of Rights passed in all 50 states. However, it wasn’t until 2021 that she explicitly named Manson as her abuser. In her statement, Wood claimed that Manson had “horrifically abused [her] for years,” including manipulation, brainwashing, and various other forms of coercion, starting when she was a teenager.

Following Wood’s public disclosure, several other women came forward with their own allegations against Manson, echoing similar themes of manipulation, psychological abuse, and sexual misconduct. Among these accusers were Ashley Walters, Sarah McNeilly, and Ashley Lindsay Morgan, who shared their experiences via social media platforms, detailing disturbing accounts of their time with Manson. These women described a pattern of behaviour that involved Manson using his celebrity status to manipulate, control, and harm them in various ways.

How Marilyn Manson Reflected the Emepheral Nature of Accountability and Justice

The fallout from these accusations was swift in some respects, with Manson being dropped by his record label, Loma Vista Recordings, and being removed from television projects like American Gods and Creepshow. Furthermore, the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department began an investigation into the abuse allegations surrounding Manson.

These accusations and their public nature have sparked broader conversations about accountability, the power dynamics in celebrity relationships, and the support structures needed for survivors of abuse. Manson, for his part, has denied the allegations, calling them “horrible distortions of reality.” His legal team has responded to various lawsuits, suggesting that these claims are part of a coordinated attack. As of now, the legal processes are ongoing, and the court of public opinion remains sharply divided on the issue.

Yet, there has been no shortage of interest in his recently announced tour. Even the name of the tour, ‘As Sick as the Secrets Within’, which shares the name of his recently released single, stings as a slight to all the women who have suffered at the pallid hand of the talc-dusted embodiment of the edgelord syndrome. The lyrics cloyingly and desperately attempt to elucidate his religious reformation while also portraying the extent of how guilty his conscience is over morose pedestrian melodies which forlornly paint Manson as the ultimate victim of his vices. He’s a different beast than he was in Antichrist Superstar, but has he really found the light, or is he attempting to use it to blind his fans from his previous sin?

Regardless of what he’s putting in his arsenal to stay relevant and put money in the bank, for as long as the industry enables abusers, women will suffer the success of artists who gain their power from popularity. Fame and fortune empower and embolden abusers, which brings to question, should musicians who have fallen from grace get a shot at redemption?

Is the Road for Redemption Open for Cancelled Artists?

The phenomenon of ‘cancelled’ artists raises intricate questions about justice, redemption, and societal values. As public figures fall from grace, the discourse often oscillates between calls for accountability and the potential for rehabilitation. This conversation becomes particularly charged in the context of musicians, where personal character and creative output are often deeply intertwined.

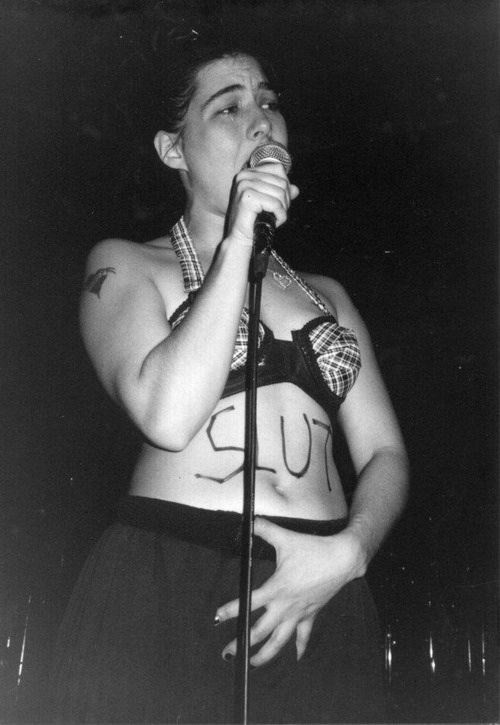

The music industry, with all its glamour and history of pushing boundaries is a sphere where misconduct can go unchecked, sometimes shielded by fame and financial influence. Women, in particular, have borne the brunt of this unchecked liberty, as evidenced by numerous accounts that have surfaced in recent years, detailing exploitative and abusive behaviours by prominent male musicians.

The #MeToo movement has been instrumental in bringing many of these stories to light, challenging the industry to confront its demons and reassess its moral and ethical standards.

The call for ‘cancellation’—a form of social ostracism where the public withdraws support for the offending artist—often follows revelations of particularly egregious behaviour. This mechanism, while serving as a tool for public accountability, does not necessarily equate to legal repercussions but aims to impact the cultural and commercial viability of the artist. However, the complexity arises when considering whether these artists should have a pathway to redemption and what that pathway should entail.

Redemption, in a cultural sense, requires genuine contrition, a commitment to change, and actions that demonstrate an understanding of past wrongs. It is not merely a public relations exercise but a profound personal transformation that must be evident over time. The public’s scepticism towards seemingly sudden transformations of troubled artists is not unfounded.

For instance, Marilyn Manson’s recent portrayal as “skinny, sober, and Christian” coincides with the release of his new album and a new record deal with Nuclear Blast Records. This raises critical questions about the sincerity of his transformation, especially given the timing aligns with a strategic attempt to revive a career marred by serious allegations of sexual abuse.

The severity of the allegations against such artists cannot be overshadowed by their attempts at image rehabilitation. Society’s eagerness to embrace a comeback story should not undermine the experiences of the victims or trivialise the gravity of the offences committed.

While forgiveness is a personal and sometimes necessary path for healing, it should not be confused with the public’s responsibility to hold individuals accountable for their actions. The entertainment industry, in its quest for profit, often blurs these lines, readily backing projects that promise financial returns, sometimes at the expense of ethical considerations.

Furthermore, the readiness with which some sections of the industry and the fan base accept such artists under the guise of a second chance can send a disheartening message to survivors of abuse. It perpetuates a cycle where financial gains overshadow moral accountability and where superficial changes are rewarded over substantive justice.

Conclusion

The question of whether fallen musicians deserve a shot at redemption is not a simple one. It necessitates a discerning approach from the public and the industry, emphasising that redemption should be rooted in real change, not just rebranding. The music industry must develop more robust mechanisms to address and prevent abusive behaviours. Ultimately, the journey back should be marked by a sincere commitment to change, underpinned by actions that speak louder than any comeback album ever could.

Article by Amelia Vandergast