With the crushed-up Carrolls packet in his hand. Anybody who uses storytelling as a distraction from our unavoidable human pain that stems from our apparent meaningless and inability to recognise the merit of love will know what he means.

Like many who see the picture of our world with an extra degree of depth, MacGowan was not only misunderstood but to many a figure of misguided disgust. As we tumble towards our annual celebration of capitalism this “Christmas”, we will no doubt see many paying tribute to the writer of their favourite holiday anthem, simultaneously swapping original stories about the horror of Kirsty MacColl’s graphic death or the fact that MacGowan was actually born on Christmas Day, but like every decoration associated with our season of pseudo community, MacGowan will go back into the attic. There he will, albeit without concern, sit with his reputation. You only have to look at the obituaries that fill the internet today to fully feel what this really means, with his dental history getting more reference than many of his finest songs and his propensity for intoxication essentially being portrayed as his primary occupation.

This week also saw the eventual death of the seemingly immortal Henry Kissinger, with the ever-divisive political advisor using his life to perfectly symbolise the poisonous circular nature of the human state. The victim becomes the abuser. The thirteen-year-old Jewish football fan who suffered beatings in order to watch his childhood passion live and therefore break Nazi segregation laws before fleeing his homeland to avoid persecution, would spend his adult life lending his unquestionably gifted mind to manufacturing policies in which unjust beatings, persecution, and forced fleeing were a constant, as well as of course, ruined childhoods. Kissinger was evil. Kissinger was a realist. The now intergenerational debate. Maybe Kissinger was just a fucking passenger who transferred his trauma as he, like so many people, did not know where to put it. The man whose youth was uprooted at such a young age, who had such graphic memories of inhumane treatment beyond his control, spent his adulthood never wanting to be so powerless again. So power became the goal, even if it involved walking over children’s bodies to get it. Otherwise, he would be a stepping stone on somebody else’s pursuit. A horrible game, life. And for all of Henry Kissenger’s intellectual prowess, his emotional shortcomings made him a mere player. This was something that Shane MacGowan was never going to be.

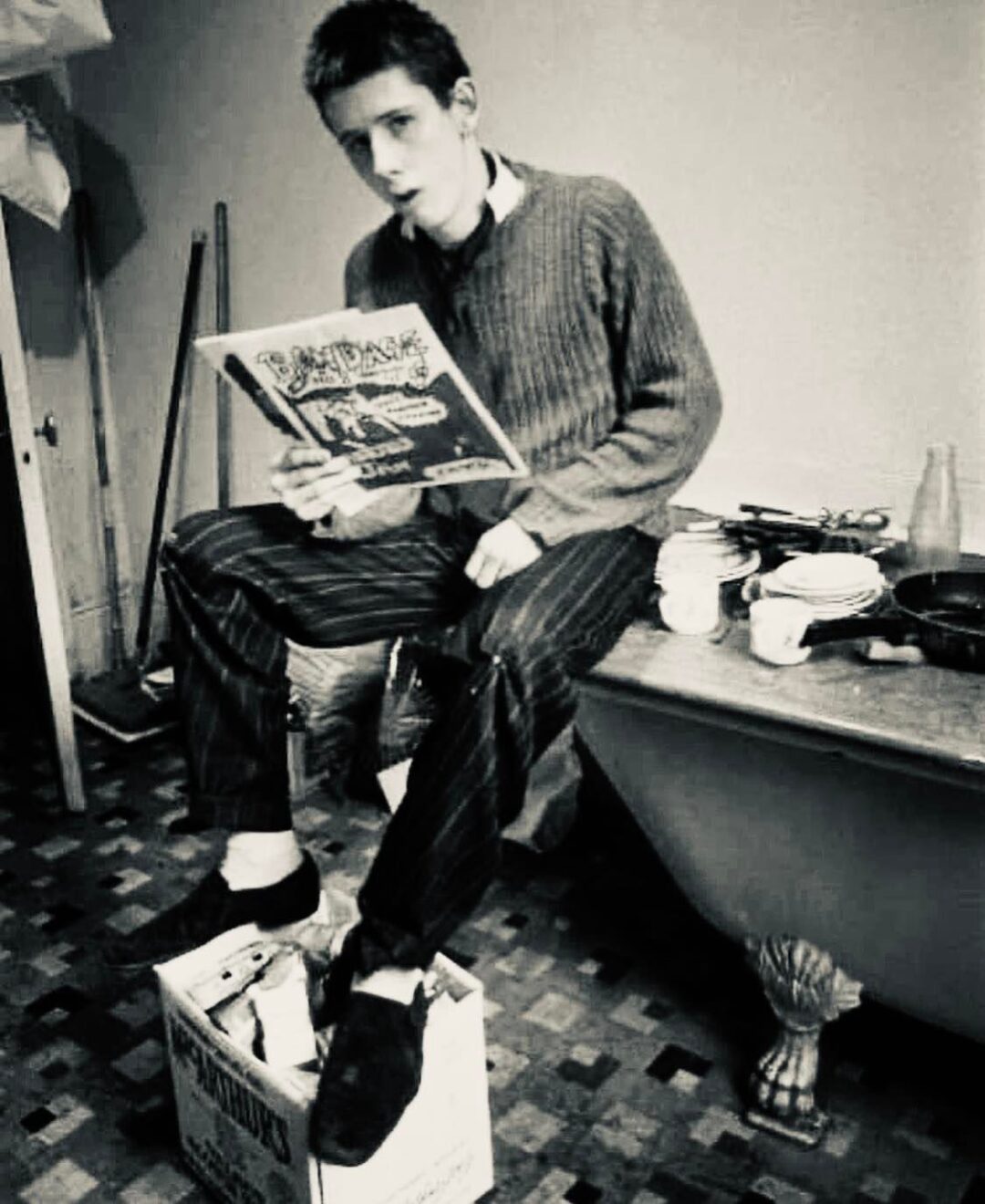

Born into a culture in which substance abuse was common ground, claiming to have developed his alcohol dependency by the age of five, MacGowan learned young that these humans we call adults are creatures of pain. Unlike the popular nuclear model in which superhero parents (many do not leave this ideology) refuse to admit their suffering whilst consistently failing to explain their passive aggression and distance, furthering the isolation of their children who begin to feel that their own negative feelings are immoral or unnatural leading to lifelong battles with closeted depression, MacGowan had an easier access to reality. After the “happy dream” of a childhood he experienced in the first six years of his life with his Mother’s family in Tipperary, which he described as an “open house” consisting of round-the-clock music sessions and a sleep where you lie policy, MacGowan moved over to his parents in the UK. This new life was a far cry from the smell of smoke and echoes of accordion that I’m going to decide made up the ambience of the Tipperary dream, and MacGowan entered hell. The folks were depressed, alcoholism was there but not the fun Irish kind that we have masterfully learned to justify, and a bit of arthritis for good measure. He claims to have exaggerated his parents’ plight out of projection of his own grim mental state on certain occasions, which could be true or just that typical Irish guilt that comes with exposing family matters. Regardless, an Irish heart now pumped in an English-based body, and as we would hear so many times over the next five decades via one of the most distinctive voices in music history, Shane MacGowan wanted to return to dreamland. A breakdown followed at the age of seventeen, as well as a six-month stint in a psychiatric hospital, which in the 1970’s, was often referred to as a “nut house”. On top of this, they would fucking treat you as such. A nutter, in a house. Medical professionals, decades your senior, treating your mental state with a large dosage of otherness, judgement and tranquillisers.

As MacGowan said himself; “This was a big thing in the 70s – there’s thousands of people in mental hospitals who were made zombies by downers.” By this point, the eighteen-year-old MacGowan had grown aware of the hypocrisy of humanity. The spiritual intelligence had been beaten into him by life. With no figures of artificial moral authority who could, with a straight face, tell the young Shane how to live, he realised that we are all vulnerable and broken. He saw through the facade and his dysfunctional upbringing taught him a vital lesson: this poisonous quest for power is just a creative denial of pain, passed down by generations of broken people trying to convince their children to be better than them by in a fucked up way, being worse than them. Be more immoral, stand over more bodies, trust less, hurt more. WIN more. With MacGowan having no such figure, the mantra became simple, hurt nobody: be yourself.

Our innate obsession to fulfil our own needs suppresses the generosity that pariahs like Shane MacGowan represent. Our fear of our inner darkness forces us to purchase an emotional armour which allows us to pour pain into the external world so that we can minimise internal anguish. MacGowan opted against such protection and selflessly shared his inner torment, giving millions a feeling of comfort. His demons were unbeatable, but unlike many of us, that didn’t cause him to join them. Gin in hand, a struggle through a ballad with a permanent face of despair, elongated gravelly vowels, these may seem like the acts of a man who is defeated, but in reality, they are the war cries of a man refusing to give up. The devil takes strange forms. On-time melodies, consistent performances, commercial awareness, ageless skin, PR savvy interviews. The devil takes strange forms. The romantic and cynic live in us all, with modern culture encouraging us to recognise neither in exchange for a character of acceptability, furthered by a society that was already suppressing individuality moving our sense of self-worth onto social media. At our core, we know this.

You don’t love The Fairytale of New York for its “Christmassy” feel or how it acts as a shopping soundtrack. It’s your subconscious that is moved. It’s a story of a human whose optimism refuses to die in the face of self-sabotage. The key word is self. Hurt nobody, be yourself. Pictures of Shane MacGowan smiling on his deathbed shouldn’t come as a surprise. “Some of them fell into heaven, some of them fell into hell.” The former is the only place for MacGowan.

Article by Michael Anthony

Listen to the Michael Anthony Show on Spotify and Apple Podcasts